Poor Will’s Almanack for 2023

Bill Felker

September 22, 2021

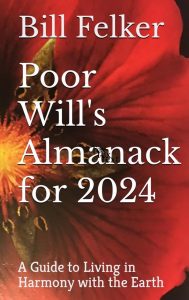

Poor Will for 2024: A Guide to Living

in Harmony with the Earth. $20.00 with Free Postage.

The most complete weather almanack available for the Eastern United States. In addition to traditional features, such as astronomical data, this Almanack contains WEEKLY WEATHER OUTLOOKS, as well as descriptions of the MAJOR COLD FRONTS OF THE YEAR. It also contains a NATURAL CALENDAR that provides dates for significant changes in the seasons.

The most complete weather almanack available for the Eastern United States. In addition to traditional features, such as astronomical data, this Almanack contains WEEKLY WEATHER OUTLOOKS, as well as descriptions of the MAJOR COLD FRONTS OF THE YEAR. It also contains a NATURAL CALENDAR that provides dates for significant changes in the seasons.

For your autographed copy, order through the website bookshop or send a check for $20.00 to Poor Will, P.O. Box 431, Yellow Springs,Ohio, 45387/

The most complete weather almanack available for the Eastern United States. In addition to traditional features, such as astronomical data, this Almanack contains WEEKLY WEATHER OUTLOOKS, as well as descriptions of the MAJOR COLD FRONTS OF THE YEAR. It also contains a NATURAL CALENDAR that provides dates for significant changes in the seasons.

The most complete weather almanack available for the Eastern United States. In addition to traditional features, such as astronomical data, this Almanack contains WEEKLY WEATHER OUTLOOKS, as well as descriptions of the MAJOR COLD FRONTS OF THE YEAR. It also contains a NATURAL CALENDAR that provides dates for significant changes in the seasons.